He probably would have done the same for her youngest child.

But on Feb. 16, 2020, just two days after he was born, two people entered his apartment, shot him multiple times and left him to die, according to authorities in Wichita, Kansas.

Investigators and those close to him believe Winston knew the people who shot him, but the killers were never identified. For more than two years, his family has waited in deep pain and frustration to find out who killed him and why.

“It’s like a hole that hasn’t been filled,” Winston’s mother, Sherby Miller, told CNN. “It’s just a part of me that’s missing because I don’t know what happened to my child.”

Winston’s death is one of many cold cases in Kansas — unsolved homicides, missing persons and unidentified remains — that investigators have struggled to solve as leads dry up and they run out of potential suspects. But the families of some of these cold case victims may soon find new hope for answers from an unexpected source: prisoners.

In an effort to find new leads, Kansas authorities have developed a deck of playing cards containing 52 of the state’s cold cases – each card displaying a victim’s photo, a brief description of their case and a number. whistleblowing line. The Kansas Department of Corrections says it started handing out the cards over the past week to people incarcerated in state jails and county jails, in the hope that some might know something about the cases and submit advice.

Cold case card games have been used in more than a dozen states, with some telltale tips that have revived stalled investigations, led to convictions, and brought resolution to families who have grieved for years without answers.

Those close to Winston were blindsided by his murder, telling CNN he was a devoted father and budding entrepreneur who was well-liked. His mother and girlfriend, Valyn Burrell, said they wanted justice for his six children, whom he adored and spent most of his free time on.

“I don’t understand. Whoever did this knew he had kids. They knew he had family. I don’t understand,” Miller said.

The families of the victims featured in the Kansas card game described to CNN a torturous wait for resolution, with some also fearing for their own safety as the killers go undetected.

But they all agree on one thing: someone, somewhere, knows what happened. And they’re hoping the playing cards will be the final nudge that gets them going.

“One day someone is going to speak and we’re going to have that break. And hopefully I’m alive and on this earth to see that,” Burrell said.

The boy who begged to stay home

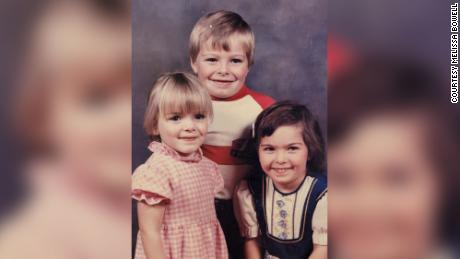

For more than three decades, Elizabeth Geer Jones and Melissa Bowell agonized over what drove someone to kill their 11-year-old brother, Nelson Louis Jones.

They remember him as an adventurous boy who exuded a mischievous, playful energy and led them through activities like jumping out of the family shed and swinging like Tarzan from a garden hose he tied to a tree.

But on the evening of October 29, 1990, one of his sisters came into his room and found him strangled to death.

It’s a day they replay in their minds, struggling to make sense of the moment that turned their lives upside down. On the morning of his death, the sisters recall Nelson asking their mother to let him stay home alone for the first time while the family visited a greyhound racing track in Wichita, about an hour and a half away. the.

When they returned home that evening, they called Nelson and received no response. Thinking he might have taken to the streets to attend a school carnival, they went looking for him, but he wasn’t there. Finally, one of the sisters checked her room.

The sisters were only 9 and 10 at the time of Nelson’s death, which caused grief from which they said their mother never recovered. “Since the time my brother was murdered, my sister and I have not had a happy childhood,” Geer Jones said.

Nelson is the youngest victim of Kansas’ cold business cards, and the sisters hope a rift in his case could hold someone accountable for his murder and bring them some long-awaited peace.

“It would reassure me because my mother passed away without knowing it, and I know the only thing she really wanted was to know who murdered her son,” Geer Jones said.

Bowell thinks knowing who did it could give their family a chance to figure out why Nelson was killed – giving them some resolve.

“I wonder if this person has a conscience? Bowell said. “Do they realize what they did? Not only taking the life of a child, but I felt like we lost our mother that day as well.”

A grandmother “paralyzed” by uncertainty

For a long time after Alex LaRussa’s disappearance, his grandmother Colleen Greenemeyer said she could hear his voice screaming as she drove past the Solomon and Smoky Hill rivers that run along Interstate 70.

“I would swear I would hear him talking to me, saying, ‘Grandma, find me, find me. I’m here,'” she told CNN.

LaRussa disappeared from Salina, Kansas, in December 2017. About a month later, police found her car abandoned by a river in a nearby town with her cellphone, clothes and wheelchair inside. He was never found.

Prior to his disappearance, LaRussa had struggled to mentally and physically recover from having his leg amputated that summer. For much of LaRussa’s life, his grandmother watched over him, occasionally bringing him to live with her and doing her best to keep in touch as he moved in and out of prison, mostly for burglary and theft. .

Greenemeyer remembers her grandson chasing his dream of playing football while living with her. When he went to jail, she said he started reading, asking her to send her bundles of books.

After LaRussa disappeared, Greenemeyer left her dream home about an hour away and returned to Salina to be close to her daughter, determined to find out what had happened. When she arrived, she said she was overwhelmed with grief.

“You’re really paralyzed,” she said. “And it’s really disheartening because I moved here thinking that I can help or get to the bottom of it – that I would do this, this and that, and we would find out and I would be persistent. And I couldn’t don’t either.”

Without the comfort of knowing what happened to her grandson, she was forced to sit with the heartbreaking possibilities racing through her mind.

“I would love for him to come knocking on my door, but I’m almost positive in my heart, deep in my being, that’s never going to happen,” she said. “Whether [we] knew he was gone, that someone had killed him and they were going to pay him, the relief would be incredible. Unbelievable. You know, we can take a stone and put it somewhere for him and honor him. Have a place to put flowers.”

Like other cold case family members CNN spoke to, Greenemeyer worried for her family’s safety. They think LaRussa may have been hurt and long after he disappeared, they feared whoever did it would target them next.

As cold case packets are given to prisoners, Greenemeyer hopes his grandson’s time in jail will increase the chances that someone who retrieves his card will recognize him and provide information.

“I believe there are people, yes, who know exactly what happened to him. They just don’t talk,” she said. “My fear is not knowing before I die. I’m 72 and I’m not in good health. … That’s my biggest fear is not knowing.”

Cards have a hit record

While it’s hard to quantify the number of cold cases solved through prison card games, officials in Florida, Connecticut and Oklahoma told CNN their games have undoubtedly led to tips. of prisoners who helped solve several cases.

“Having their loved one on that bridge and hoping that a tip can generate other leads is the hope that this family is holding back,” Fahey said.

Florida no longer has a cold case card program, but the state had almost immediate success when it released its first games in 2007. Within a year, investigators were able to proceed to arrests in two of the game’s cases after receiving tips from prisoners, Florida Department of Law Enforcement spokesman Jeremy Burns confirmed.

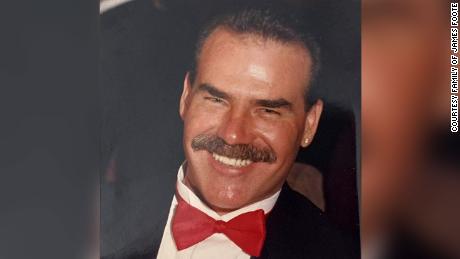

One of the cases was that of James Foote, 53. An easy-going man with a good sense of humor, Foote could talk to anyone, his family told CNN. Foote was retired and living in Florida with his family at the time of his death. In retirement, he began to obsessively pursue hobbies like fishing, golf, and, at the time of his death, karaoke.

On the night of November 15, 2004, Foote was heading to a bar for karaoke night when someone shot and killed him. After months of investigation, detectives at Fort Meyers ran out of new suspects and the case went cold.

After nearly three years of trying to find new leads, authorities received a letter from a prisoner who saw Foote’s playing card. Investigators would learn that at least four prisoners heard a man named Derrick Hamilton bragging about killing Foote.

In October 2007, Hamilton was arrested in connection with Foote’s murder. He did not contest a charge of second-degree manslaughter and was sentenced to four years in prison.

Foote’s wife, Donna Foote, describes the years of waiting for answers as “torture”, but she believes the playing cards were essential to solving the case.

“I don’t know if it would have been resolved any other way,” she said. “I totally give all the credit to the cards.”

CNN’s Amanda Jackson contributed to this report.